by EMEKA OKONKWO

ABUJA – THE former Nigerian president, Muhammadu Buhari, who has passed away in a London clinic, joins an unenviable list of sitting and former African heads of state who die abroad while seeking medical attention.

This trend is mostly a result of lack of investments and corruption by the governments they led, thereby paralysing the health sector.

It is a development infamously referred to as medical tourism, which sees the political elite travel outside the country, mostly at the expense of state coffers.

A majority of people are left behind at the mercy of ill-equipped hospitals contending shortages of specialists, drugs and medicine as disgruntled health workers search elsewhere overseas for greener pastures.

“Our leaders keep dying in clinics far from home. When will they start trusting hospitals in Africa or their own countries?” queried Hopewell Chin’ono, the award-winning journalist and socio-economic commentator.

“What does it say about the integrity of African institutions when the political elite do not even trust the very systems they superintend?” Chino’ono, a critic of governance in Africa, commented after the death of Buhari.

Buhari, a military ruler in the 1980s, who bounced back as a civilian leader between 2015 and 2023, died this past weekend aged 82 in London, United Kingdom.

His death has been blamed on prolonged illness.

In 2017, Buhari spent over seven weeks in the United Kingdom for what the government described as “routine medical check-ups.”

He had earlier complained of an ear infection.

Under Buhari’s tenure and that of the current government of President Bola Tinubu, doctors at public hospitals are intermittently on strike over poor wages and working conditions. Many doctors are seeking better opportunities abroad.

Africa’s history is littered with a number of sitting and ex-presidents passing away abroad while seeking health care, which is better than their countries. Such leaders are complicit in the poor performance of their health systems.

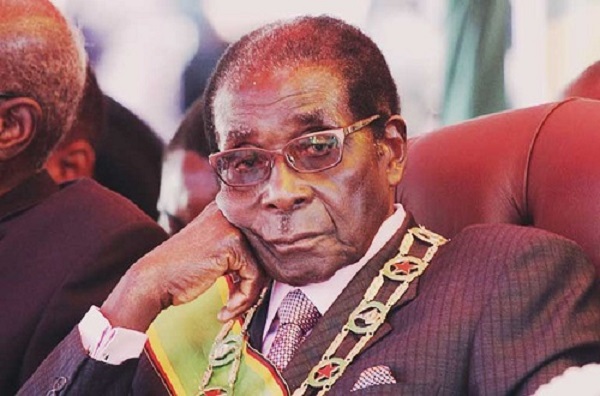

Most prominently is former Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, who died in Singapore in 2019, aged 95.

At independence in 1980, Mugabe’s government inherited a viable health sector but because of the scourge of corruption, years of mismanagement of the economy and doctors leaving for better opportunities, the sector is a shadow of its former self.

Some of Mugabe’s ministers died in neighbouring South Africa.

Zimbabwe’s elite afford such luxury as treatment outside the country. They can afford it. A majority that have fled to South Africa cannot. In recent weeks, some South African pressure groups have barred Zimbabwean and other foreign nationals from accessing health care at public clinics and hospitals.

Largely because of the mismanagement by the government, Zimbabwean hospitals have recently lacked such basics as painkillers, bedding and water.

Doctors have on many occasions held strikes over low wages and poor working conditions in a country synonymous with hyperinflation.

Other sitting and ex-presidents that died overseas are Omar Bongo (Gabon), Lansana Conte (Guinea), Jose Eduardo dos Santos (Angola), Pascal Lissouba (Congo), Levy Mwanawasa (Zambia), Malam Bacai Sanha (Guinea Bissau), Michael Sata (Zambia) and Ahmed Sékou Touré (Guinea) and Meles Zenawi (Ethiopia).

Gnassingbé Eyadéma of Togo died in Tunisia aboard a plane en-route to a hospital overseas.

John Atta Mills (Ghana) and Nigeria’s Umaru Musa Yar’ Aduwa have succumbed in their countries but after medical stints abroad.

However, there have been incidences of African leaders dying outside their countries but within the continent.

Most recently is the former president of Zambia, Edgar Lungu, who passed away in South Africa in early June. He was undergoing treatment at a facility in the capital Pretoria.

Kamuzu Banda, former Malawi president, also died in South Africa.

In Zambia, the country is gripped by a scandal in the health sector, after an audit exposed deep-rooted malpractice in the procurement and distribution of medicines, with evidence pointing to long-standing systemic abuse and theft of public resources, including medicines.

The current ruling party, in power since 2021, argues it inherited this scourge from Lungu’s government.

While most of the deceased political leaders’ remains are repatriated, Lungu’s family plans to bury him in South Africa, in an ongoing deadlock between the family and the government back home over funeral and burial arrangements.

Former Malawian President Kamuzu Banda

He would not be the first ex-African head of state to be buried outside his country.

Longtime dictator of the then Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo), Mobutu Sese Seko, was buried in Rabat, Morocco, where he died in exile in 1997.

The then First Lady of Gabon, Edith Lucie Bongo, also died in Rabat, in 2009.

Guzha Spencer Shorayi, another commentator, said the death of politicians while seeking treatment outside their countries was “pathetic” and “insane” of these deceased leaders.

“What kind of leadership is it that you don’t even trust the systems you watched over? It goes to show that they know the systems are broken down, hence they look for alternatives. They know they broke the systems,” Shorayi said.

Last year, Human Rights Watch and the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights lamented that African governments are falling far short in their commitments to prioritize public spending on health care.

Thus, the governments are failing to meet a target of allocating at least 15 percent of their national budgets to improve health care, as per their pledge under the 2021 Abuja Declaration.

On average, the rights groups report that African governments spend only 7,4 percent of their national budgets on health care, less than half of the pledge.

– CAJ News